Nerve cells proliferate like crazy when we are young but this slows down as we approach adulthood and the emphasis shifts from making new neurons (grey matter) to making new connections (white matter). Once adult, accelerated loss of neurons becomes a hall mark of diseases like Parkinsen’s, Alzheimer’s and diabetes and of aging, traumatic injury and stroke. Unfortunately, adult brains have very little ability to compensate for the loss meaning that in most cases the damage is permanent. Naturally there is great interest in exploring the possibility of using transplanted nerve cells to replace those that are lost.

There is another group of people who have a different interest, namely intelligence amplification and cognitive enhancement. Learning in infants proceeds by guided selection and attrition from a large pool of redundant neurons and synapses. This is what gives a three year old the amazing ability to learn simply through exposure to the world. As adults we use a completely different learning strategy. If it were possible to restore/recreate the original dense neuronal matrix of an infant but in a specific area, targeting a specific cognitive function, then by engaging in a selective learning task we could conceivably acquire new talents rapidly at any age, and possibly without limit. A biohacker’s dream.

Is such a thing possible and can neuron transplantation enhance cognition? Obviously an enticing question although a definitive answer is in the future. For now check out this article by Stephen Frey in Cogtech. What I can say is that cell biology is advancing at a blistering rate, crispr gene editing is an example. In my view advances in biotech are beginning to allow us to direct our own evolution and neuron transplantation science is one of the onramps along that highway. What is the future for human neuron transplantation? The following is a look at where we are now and what is soon coming.

Embryonic Neuron Transplants

The first targets one thinks of for neuron transplants are diseases like Parkinson’s disease (PD). The loss of movement control in PD is due to the death of neurons in two midbrain regions (the substantia nigra & striatum), regions that use dopamine as neurotransmitter. An obvious way to correct the movement problem is to simply replace the sick neurons with healthy ones. Early attempts at this, beginning in 1987, involved surgically grafting human fetal brain tissue rich in dopaminergic neurons into the striatum of PD patients. Although the results were highly variable, some patients did see improvement in motor performance meaning that the graphted fetal cells survived at least for a time sufficient to restore dopamine release in the target area. There were, however, serious complications and while encouraging, the use of human fetal tissue comes with loads of medical and ethical problems. The partial successes do show that there is a great deal of neuroplasticity that might be tapped to help Parkinson’s sufferers. The search is on to find better ways and more consistent results.

Stem Cells

Neural stem cells (NSCs) are self-renewing cells that generate the neurons and glia of the nervous system during normal embryonic development. Some neural stem cells persist in adults and continue to make neurons & glia throughout life, but only in limited regions, in limited numbers and with very little ability to repair damaged tissue. To use stem cells for transplant you have to find a way to gather lots of them. Human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) seem a logical way to go because they can be made to proliferate in culture. Here is the hard part, the grafted cells have to survive transplantation, escape immune rejection, express the correct biochemistry, and make appropriate, persistent and functional synaptic connections. And then because embryonic stem cells are by their nature pluipotent, meaning they can differentiate into almost any cell type, there is the risk that grafts will become tumors (teratomas), plus the process also comes with a myriad of ethical problems.

There are some notable successes with transplants of hESCs, especially in the eye, which is of course part of the central nervous system. Grafting restores a degree of visual acuity after injecting hESCs into the eyes of people with severe vision loss. One reason this works is that the eye does not show a strong immune response to grafted tissue. Nowadays, stem cells can be collected from the retina itself, cultured and driven to behave like photoreceptor cells, an approach that avoids the ethical constraints; possible good news for people suffering from macular degeneration. But before using stem cells to treat disease in a more general way we need to know more about how to control cell proliferation and the factors that regulate their differentiation into specific neuron types. These are big hurdles, but read on.

Cell Reprogramming

Remarkably, mature cells, for example cultured skin cells (fibroblasts), can be reprogrammed to behave like embryonic stem cells. These induced stem cells can then be guided into becoming specific types of neurons, for example dopamine neurons, and used for grafting. This is really cool science and it opens up a new world of possibilities. It means that neurons can be produced using cells from the very same individual who will receive the transplant, removing two hurdles, immune rejection and the ethical issues associated with embryonic stem cells. As of now, dopamine neurons have been made from human fibroblast derived cells and injected into substantia nigra of rodents with Parkinson’s symptoms with the result that motor control is improved. And there is still more.

Functional neurons can also be generated by reprogramming without ever having to go through a pluripotent stem cell stage which eliminates the risk of tumor formation. But whether dopaminergic neurons created in this way survive transplantation, grow in the patient’s brain and improve motor function isn’t known yet for either animal models or humans. The method is promising, but there are lots of things that have to be sorted out.

Addressing the Wicked Problems

Wicked problems are the extremely complex ones, those with a huge number of variables that are difficult to recognize, and complicated by incomplete or conflicting data. They are wicked because they’re difficult not because they’re evil. One example is “The nature of consciousness”. Transplant therapy involves a number of wicked problems, one being the need to assess the efficacy of transplant.

To succeed the grafted cells don’t just have to survive, they have to integrate into the existing neural network by recognizing and responding to the local cellular environment. They have to make correct synaptic connections with neurons sending information to the network, process that information appropriately and send it on over the correct pathways to target neurons elsewhere in the brain. To pull this off, the graft has to express the right biochemistry, adopt the right cell signaling and cell recognition pathways and tons more (read more here). Any reasonable engineer would just say ‘forget it’. But the important thing to remember, as Jell Goldblum pointed out, is “life finds a way”. For stem cells, adaptability and plasticity is the way.

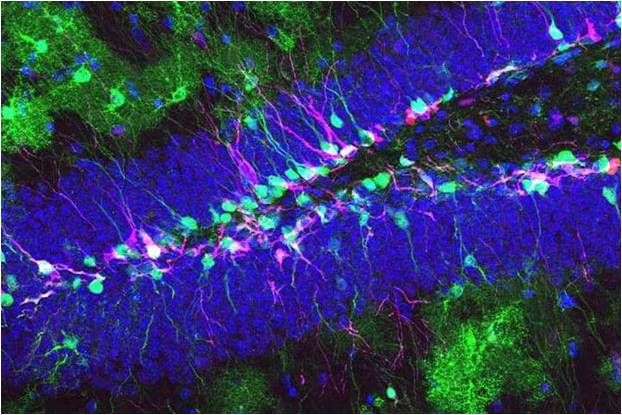

The successful integration of fetal neurons transplanted into the visual cortex of adult mice is an example of this remarkable plasticity. Susanne Falkner et al. transplanted embryonic nerve cells into lesioned areas of the visual cortex of adult mice. The transplanted cells survived and made the same kinds of synaptic connections that neurons in their position normally make. They responded to visual stimuli and formed appropriate functional connections with nerve cells all over the brain. In fact, the grafted neurons received the same inputs as their predecessors in the network, processed the information and passed it on to the correct downstream neurons. This amazing result says that, at least in mice, there is enormous potential for repair in visual cortex. For now, we can’t do this kind of thing with humans for ethical reasons. But it makes you wonder if a similar degree of plasticity exits in human cerebral cortex because if it does the applications go way beyond damage repair in the direction of cognitive enhancement. Is this a fledgling first step toward “directed evolution”? Enough to make you think.

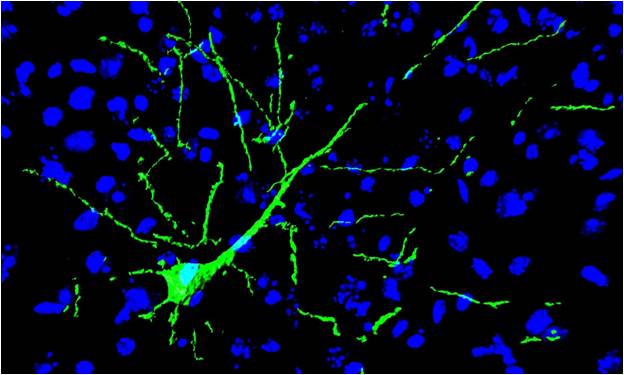

A transplanted induced neural stem cell (green) fully integrated in the neuronal network of mouse brain (blue) (credit: Luxembourg Centre for Systems Biomedicine)

Here are some of the provocative successes of neuron grafting that point toward our future:

Human Neuron Transplants Treat Spinal Cord Injury in Mice (reference)

Human stem cell-derived neuron transplants reduce seizures in mice (reference).

Stem cells able to grow new human eyes (this is like something out of Blade Runner, reference).

Stem cell injections help stroke victims walk again (reference).

Stem cells help paralyzed victim gain use of arms (reference).

– neuromavin