“Wrinkles should merely indicate where smiles have been.” ~Mark Twain, Following the Equator

The idea that we could lose access to the memories that are so important to our identity and connection to the world as we age is a haunting fright conjuring the demon of Alzheimer’s dementia. It is also the driving force behind an industry of memory products touted to hold the demon at bay, although they mainly seem to heighten the anxiety. We can choose to be proactive and decide how we wish to embrace aging while maintaining high cognitive function; my personal choice is to stay mentally playful and pursue novelty. But it would be very cool to know what is going on in our brains as we age, and perhaps learn something along the way to help approach the whole inevitability thing more gracefully, because dementia is not normal aging, although memory loss is.

Researchers at Northwestern’s Feinberg School of Medicine coined a new term for people who remain mentally sharp well into their 90’s. They call them “SuperAgers”.

The notion that some people, for some reason, escape the cognitive decline characteristic of aging is provocative and makes you wonder how they do it, or whether they have any say in the matter at all. The idea brings up a lot of questions. How should we define a SuperAger? Are such people unique or do they represent just a portion of a continuous spectrum of human diversity? Does brain imaging have something to add to the story of how the diversity comes about, or does it merely illustrate diversity in a different way, one that may or may not compliment the behavioral, genetic and molecular research that is being done? The authors of the paper in J. Neuroscience have every right to hope that their analysis captures lots of interest and promotes credible research that sheds new light on the cognitive aspects of aging; a topic that interests everyone. SuperAger is a catchy term that has garnished a good deal of instant press. Let’s see what this is about.

First, how were SuperAgers selected for study? The answer to this question defines the term. The study at Northwestern focused on a previously identified group of people over 80 yrs. old who were found to have episodic memory function at a level equal to, or better than, individuals 20–30 years younger. The group included an octogenarian attorney, a 96 yr. old neuroscientist, a 92 yr. old Holocaust survivor and an 81 yr. old, pack-a-day smoker who drinks a nightly martini. You get the idea.

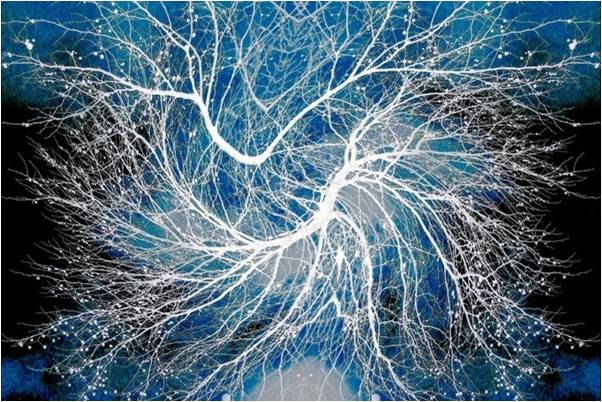

MRI imaging and anatomical data collected posthumously showed that the structure of SuperAger brains is distinctly different than what is commonly seen in people of the same age. There are three consistent differences, and together they tell us that the SuperAger condition has a visible biological signature in certain parts of the brain.

The cerebral cortex thinning and loss of volume that occurs as we age is considered to be an uncool but unavoidable part of the process. It results from a decrease in gray matter; either a decrease in the number of neurons and glial cells or a decrease in the volume occupied by dendrites. However, SuperAgers are less susceptible. The anterior cingulate cortex of the SuperAgers (31 subjects) was significantly thicker than the same area in aged individuals with merely normal cognitive performance (21 subjects).

In addition, Analysis of the brains of five SuperAgers showed the anterior cingulate cortex had approximately 87% fewer tangles than age-matched controls and 92% fewer than individuals with mild cognitive impairment. Neurofibrillary tangles, twisted fibers consisting of the protein tau, are considered to be an important factor in the development of Alzheimer’s Disease,although their exact role, and how they affect neurons is still controversial.

A really fascinating finding is that the number of VEN neurons in the anterior cingulate was three to five times greater in SuperAgers than in age-matched controls and individuals with mild cognitive impairment. This bears looking into.

VEN neurons are concentrated in anterior limbic areas. Their greater abundance in SuperAgrs may contribute to the greater thickness of the anterior cingulate cortex. They are also vulnerable to neurodegeneration which makes their persistence in “Supers” all the more interesting.

The von Economo neurons (VENs) are found chiefly in layer five of the anterior cingulate and frontoinsular cortices. They are referred to as projection neurons because their very long axons connect cortical subsystems over large distances. Differences in the density and location of VENs have been linked to dementia, autism and schizophrenia. They begin to appear in newborns at four months, but don’t start to work until about age two, which is precisely when our social emotions begin to develop. Late development means that VEN neuron expression could be susceptible to the newborn child’s social, nutritional and physical environment. There are concentrated in an area that is exquisitely sensitive to the emotional reactions of others and in regions that are activated by difficult moral dilemmas, funny jokes and moments of self-control. Bottom line: VEN neurons appear to play a crucial role in the rapid transmission of behaviorally relevant information related to social interactions.

How do SuperAgers see Themselves?

SuperAgers have stories to tell that are very informative. First, they have more energy than most people their age and they share a positive, inquisitive outlook. They often appear to have a vibrant presence when you meet them. They take on social roles, for example looking after others or helping to organize activities, and they take their roles seriously and with dedication. They often report feeling young-inside and that they grasp things quickly and remember what you tell them in a social setting. We all know people like this and society shows great respect for celebrities who have these traits. The great mystery is; how come some people are like this and others are not?

What SuperAgers report about themselves is also very telling for neuroscience. When you hear about sharing a positive, inquisitive outlook and showing ambition to remain socially engaged immediately makes you think about a healthy VEN neuron subsystem. Research has linked a positive attitude with overall health and suggests that people who are cognitively active and socially engaged have a reduced probability of developing Alzheimer’s Disease. This is based on correlations, of course, so there is no clue as to which comes first – a healthy brain or a great attitude. But even as a correlation, it makes a powerful suggestion about how best to approach aging in our own lives.

So, is it genetics or is it chance?

The brain has the characteristics of a complex system by right of an abundance of emergent properties. Aging is also complex and so far the study of SuperAgers has shown us just one dimension. There are likely to be many factors involved, and like every other human physiological process, aging will certainly turn out to be a complex genetic process involving hundreds of genes with heritage playing a big part, too.

Almost 40 % of people over 65 experience some degree of memory loss. When there is no evidence of a medical condition that might account for it, it is simply labeled age-associated memory impairment, and considered a part of the normal aging process. But is there really an inevitable loss of memory as we grow older? After all, the idea is just based on a correlation and says nothing about cause. I think the study of SuperAgers can help change the focus, and there may be many more SuperAgers than we suspect, many more people to learn from.

We each age in a different way and at a different rate. Your calendar age does not reflect your physiological, mental or cognitive age, and it is these that determine how well your body functions both physically and mentally. In fact, chronological age is almost always poorly correlated with function and capability. I think you know this to be true.

I like this quote from Caterina Rosano, Associate Professor of Epidemiology, Univ. of Pittsburgh, “What I’d really like the public to understand is that you are not destined to decline as severely as you think, there’s a lot we know about factors that affect this specific portion of the brain. Physical activity is very, very important. And it’s not like you have to go to the gym and jump on the treadmill for hours, just walking to church or gardening can be enough to make a difference.”

This prompts a really interesting question: Can we use body and mind to influence the aging process? That is worth looking into.

-Neuromavin