Whenever I go on a road trip to someplace new, the return journey always seems shorter, often dramatically so. The weird thing is that the trip home feels quicker even if the chronological time is identical. I am sure you have had this experience. It is known as the return trip effect but how this perceptual shenanigans comes about is not so very clear. One clue is that I don’t experience it when I travel a familiar route, like my commute. Since everything about the route is familiar, maybe the routine itself ensures that my expectation of travel time is the same each way, every day.

For an unfamiliar trip the conventional thinking is that on return we recognize place marks along the way that we saw on the outward journey. This makes the return trip feel familiar and somehow changes our perception of elapsed time. However, that is simply incorrect. The return trip effect applies and the return route doesn’t matter one bit as long as the travel time is similar. This was shown quite clearly in experiments by Niels van de Ven et al. So both familiarity and a simple time keeper are excluded and we have to think of a different explanation.

The de Ven group offers this idea, we tend to be over enthusiastic and optimistic at the beginning of a trip so when we finally arrive we feel that it took longer than expected. “Are we there yet?” is a question we have all heard. That feeling breeds a kind of pessimism that carries over when preparing for the return home. “So you start the return journey, and you think, wow, this is going to take a long time.” You overestimate how long the return will take, and when you do arrive home it seems quicker when the actual travel time.

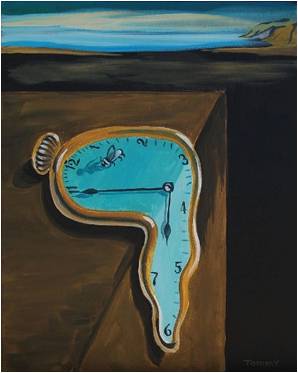

Salvador Dali

Salvador Dali

Our confusing relationship with time

It appears that we keep track of time using several kinds of mechanisms. Some track time as it passes, perhaps based on the rates of firing of neurons and mechanisms for counting the number of firings in a given period. An example is something we know from jetlag, the circadian clock that coordinates metabolism with the day-night cycle. The cellular/molecular mechanism of the circadian clock is fascinating, read more here. Another kind of clock is based on narrative, looking back on an event we construct a story about how long it took. Support for narrative clocks in the return trip effect comes from the work of Seno et al. Joseph Stromberg put it this way, “the return trip effect has something to do with hindsight and storytelling; something about the way we use language to remember an experience when looking back on it”. He would say that in order to experience the return trip effect, you need to know that you’re on a return trip.

Now we find ourselves toying with something new, the idea that the return trip effect is postdictive, meaning an explanation after the fact, one arising from hindsight bias. To address this, we need to look at how we perceive time.

We all appreciate that time is a subjective experience, stretching and contracting in ways that don’t conform with the workings of a clock, whether mechanical or biological. The reason for this is that time is not a sense, like sight or hearing are senses. Instead it is a perception subject to lots of cognitive loading. Under most circumstances we are not good at judging the passage of time and are easily distracted by other things, our mood or what we’re doing at the moment. I view the distraction is an absolute blessing. However, we are super good at telling time in other circumstances. For example, you can tell the direction from which someone is approaching from the difference in arrival time of footsteps in your two ears even though the difference is but a fraction of a millisecond. That’s a blessing, too, but it doesn’t help to explain the return trip effect and neither does the circadian clock in our heads.

Time is a big puzzle. Our perception of time is a big puzzle. Even what it means to simply say we perceive time poses difficult questions at the intersection of neuroscience, psychology, philosophy, metaphysics and causation. I started out curious about the return trip effect but found myself caught up in much more. If you are interested in cognitive neuroscience and want to explore time further, here is a good place to start.

– neuromavin